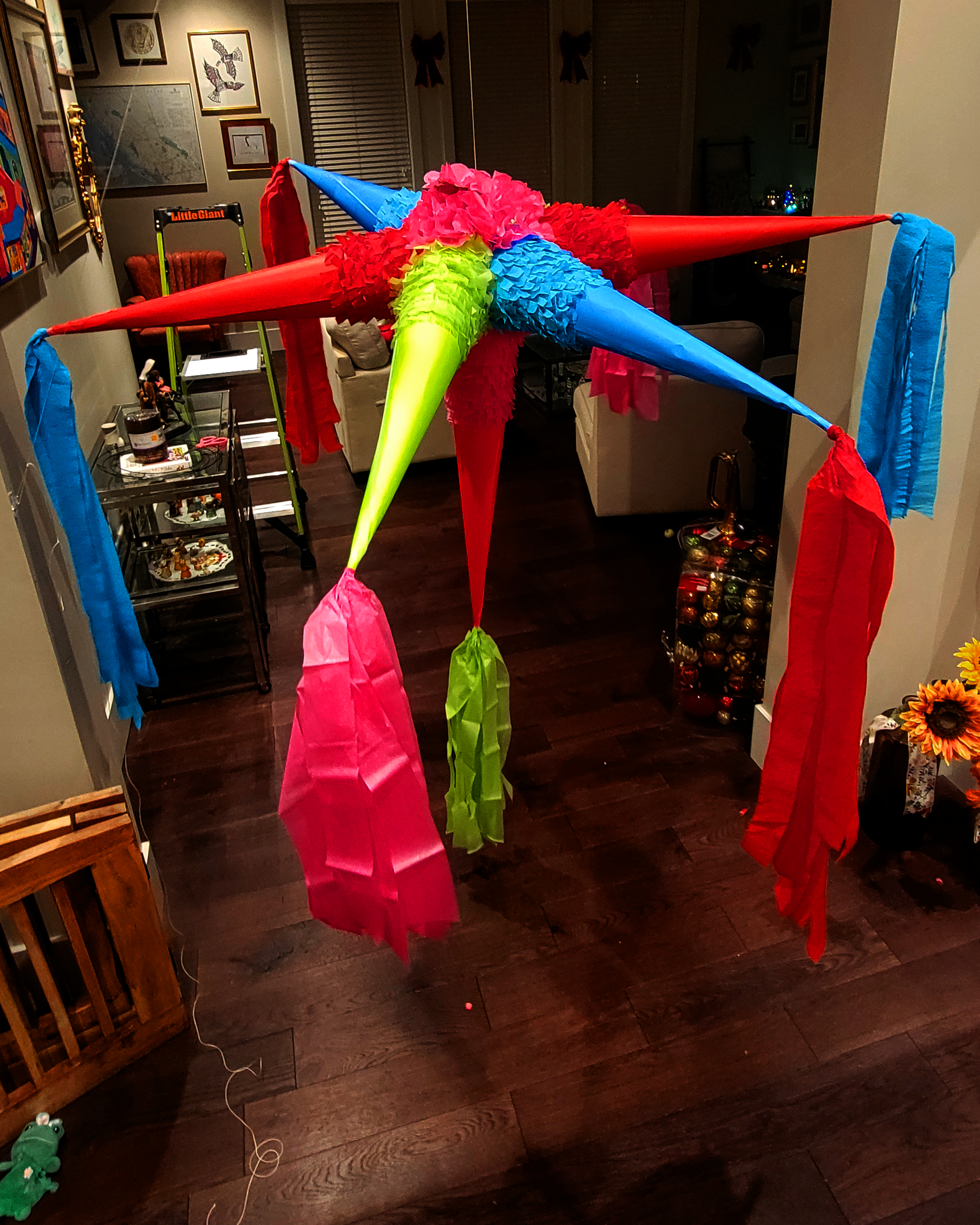

Candies That Take Forever to Chew

2025

Sometimes I’ll still look up, as if they were still there. Just grazing my head I still feel their tails, illustrating the sky without discretion.

They captivate my space, They are spectres strung up before me.

Their points jut at me, extending and retracting, reaching.

Seven summits, each point adorned with veins of filigree, its body sweeps the air around me. They say that their beauty is temptation, examples of the allure of sin.

But, I can't see that now.

The stars themselves are emancipated from their history, defiant in their authenticity. They exist in a liminal space visible but somehow not there, they are relics, absent reminders of the past.

Streaming vibrant trails as they trace parabolas above our heads. They dance erratically, off tempo from the music I can barely hear, evading me, taunting me.

If only for a moment I am captivated, held myself within the star's hollow shell, cradled in its fragile body. They are strung up before me, built to be broken, broken to be taken.

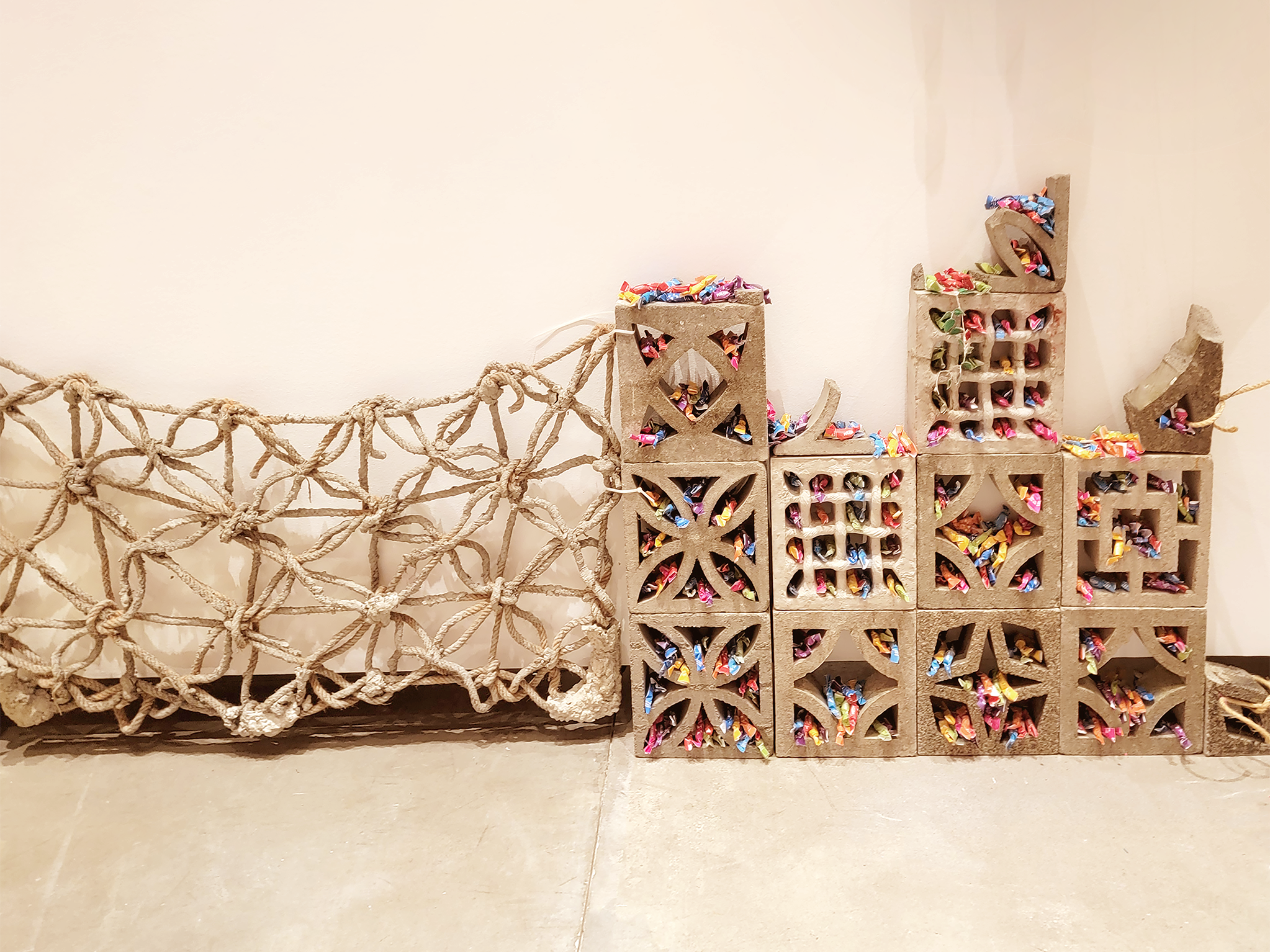

Quebra Sol

2024

Looking through old photos and home videos I find moments that I was not present for but still I lived. Repetitions of experiences, enacted by my siblings, my cousins, my aunts. I see images of piñatas, ones I never broke, because I wasn’t born. But I guess I still know how they ended. I see the piñata, as a star, then a bull, then a lizard, then dumbo, then daisy duck, shapeshifting as if I wouldn’t recognise it. After all this time, I think I’d know it anywhere. I see guidance, as a toddler’s hands grasp the bat for the first time and supervising eyes guide them to their first hit. I see anticipation that eye remember. I see my grandma’s yard in every year I could imagine. The steps are still the same. In a way it feels like the parties I never lived through and the posadas I’m living past exist in the same space.

Line after line, turn after turn, brick after brick.

Transfiguring, transforming, translating.

The piñata takes on different forms at different times.

It translates time as it breaks and reforms in my grandmother’s garden.

In all its iterations I still recognise it.

Line after line, thread after thread, sweet after sweet.

My eyes lead to my hands as they grasp my swing.

My eyes catch the piñata as it dances above me.

I see anticipation that eye remember.

Estrellas

Ongoing

At my cousin’s Posada, we didn’t really know the lyrics to the song. Some guests didn’t speak Spanish, and the only piñata we had was a Finding Nemo piñata that our aunt had given to my cousin when she was a kid.

I think about how this was the last piñata we had that was made in Mexico, in a way I felt that the place of Mexico City was sealed inside it for fifteen years. For all I know Mexico City was still active inside it. Unobserved, the quarter cubic metre of city air inside still resonated with smells, sounds, and feelings from the city that my aunt had sealed away for us. When we opened it, I wondered if it was lost? Maybe now a small quarter cubic metre of Mexican dense air still roams Vancouver. Maybe its assimilation allowed for the whole of Vancouver’s air to get just a little bit closer to Mexico?

If I make a piñata I hope that the roaming quarter cubic metre puff of air might find its way back into my papier mâché mess of a creation, at least for a bit. Since I'll never know for sure, I think I'll always act like it has come back to me. Each piñata with its potential to be holding that same air will hold in it a little bit of that place. I'll have a small part of the city with me.

Offrendas

2020, Acrylic on Canvas

I think about how I don’t really make piñatas anymore, if I ever tell this story to future generations will it have no meaning? If they have never broken a piñata does it even make sense? Will they even pick up the candies if they fall? Will I just stop telling the story because I find it too tedious? Even as I write this the ñ does not appear on my keyboard and I don’t know the shortcut to type it, I just copy it from another document and paste it in –this act is becoming draining and I can feel myself losing the want to make sure that piñata is even spelt correctly– how will I have the motivation to continue to explain it? I hope that I start making piñatas soon because I’m afraid that these stories will pass away with me.

Pateñt

2020

A piñata sits in an empty garage hanging from a tattered rope and teetering in the absent wind as it awaits the moment of collision that bridges and ruptures narratives of tradition.

Growing up in a Mexican immigrant household with 5 kids I saw a constant stream of piñatas of every size and shape being built and destroyed every year. The piñata became intimate to how my family celebrated and became a strong connection to Mexico for me, piñatas no longer represented remnants of religious tradition within my family but rather became a relic of another nature. In this project, I wanted to examine the cultural symbol of piñata that I recalled from childhood and recontextualize it based on the tradition and history of the piñata and its role within my experience.

A couple of years ago I came across a document that, for me, emblemized the shift of piñata from an object of intimate handmade family experience into a mass-produced object that bears no resemblance to its origins. I found this document when doing my research and I became fixated on it. It was a patent for an American company that explained how to make piñatas in the most cost-efficient way. The patent from 1976 claims ownership over the piñata as a hollow-bodied object and reduces the tradition of the piñata into legal jargon while never acknowledging its Mexican origins. Furthermore, the document, while ignoring the history of the piñata, also failed to include the ñ in the word piñata.

After reading the document, I was so shocked that the erasure of Mexican culture went so far that the document itself couldn’t even spell piñata properly -as if naming it would give it too much dignity- so I decided to begin by reintroducing the ñ into the document, not just in the word piñata but also in the word patent and wherever I felt it needed it. I began to redact the patent in an attempt to remove the legal narrative while revealing the Mexican narrative of erasure and appropriation. I began to reintroduce the Mexican narrative through inserting Mexican aesthetics into the diagrams, by doing this I hope to make the alien-looking diagrams of hollow spheres seem more familiar and accurate to what I know as an authentic piñata.

“The – hollow – groove – extending -- The hanging -- groove -- tied therein -- the piñata when – mentioned – manufactured – body – piñata -- the -- body is – taken” – Excerpt from redacted patent

The finished redacted document stands as a dissection of the process of erasure; reveals the eerie language that regards piñatas as body’s being hung up and taken. By revealing the language of abuse towards the piñata, we can see how the patent disregards the reality of the piñata and in this absence of reality is where the Mexican narrative starts to develop. It is through its reinsertion that the Mexican nature of the piñata is able to begin to reclaim what has been taken.

These documents showed me the reality of how the archive can conceal and reform the truth. It hides all evidence of severance from tradition and replaces it with language that places the piñata within a legal system it was never meant to inhabit. The act of archiving separates it from the home and allows it to rot as it thinks of the vestiges of the family it was once a part of.